Table of Contents

History Spells the DSLR’s Demise - chapter VI - 1990s - The age of change and denial

© Copyright Khen Lim, 2013. All Rights Reserved.

see also:

1990s - The age of change and denial

Minolta Maxxum 7000, 1985

Copyright soundadviceblog.com

Minolta’s Maxxum 7000 (1985) was a serious disrupter. From 1985 to 1990, the Maxxum 7000 and its sibling models forged a new direction and defined SLR-type autofocusing. Minolta transformed the whole industry and created a new market segment that inspired adherents that copied its approach. In the process of doing so, Minolta had also saved its own skin.

About five years earlier, the company was on the brink of a collapse. Its X-series cameras were not selling as well as they needed to. With that hanging over their heads, the Maxxum’s commercial success couldn’t have come earlier and once they knew they were on the right path, Minolta worked closely with Sigma to quickly develop a huge range of AF lenses to complement their AF-SLRs. And suddenly they found themselves becoming a market leader and an industry technology benchmark. The world was at their feet and everyone was lapping it up. As obvious as the AF-SLR was in terms of where the 35mm SLR was headed, market enthusiasm was tempered by conflicting opinions from some of the leading names in the camera business. Therefore it wasn’t necessarily an overwhelming automatic choice. It’s not difficult to see this impasse as something resembling the resistance to shift from roll-film TLR to the 35mm SLR.

Maxxum 7000 magazine ad

Image courtesy of Konica Minolta

Here’s the interesting thing again. Market perception of the AF-SLR was very positive. Many users were trading in their earlier camera kits and moving up to the AF-SLRs. The market simply grew, recording impressive sales numbers for not just Minolta but also Nikon and Canon including Pentax. There were of course also big impulse sales of the AF lenses and electronic flashes. Yet there were companies that doubted the long-term viability of the autofocusing technology and they did so purely from a technical perspective. But then again, so did the Europeans when they refused to move from the TLR to the 35mm SLR.

Like the Europeans almost twenty years ago, those who opposed the AF-SLR movement cited compromises that afflicted image quality. Because of the opto-mechanical architecture of the AF-SLR, the drive system stayed within the camera body but the gearing mechanisms needed to be integrated inside each and every AF lens. According to the detractors, these mechanisms brought unwelcome and unacceptable compromises that would mar the optical quality of the lens.

Those whose opposition to the AF-SLR was most prominent were Leica and Olympus. The others in the industry essentially sat on the fence because they were unsure of their own directions or just decided to gradually drop out of the picture. In the end, the industry was characterised by four distinct groups:

| Group 1 | Those who embraced the Minolta AF-SLR approach | |

| Examples | Nikon | F501, F401…F4s |

| Canon | EOS 620, 650…EOS 1 | |

| Pentax | SF-X, SF-Xn… no pro-grade models | |

| Group 2 | Those who resisted the Minolta AF-SLR approach for pro use but relented for consumer-use cameras | |

| Examples | Olympus | OM707AF |

| Group 3 | Those who opposed the Minolta AF-SLR approach outright |

| Examples | Leica, Rollei, Fujica, Ricoh |

| Group 4 | Those who went their own way with a different AF-SLR approach | |

| Examples | Contax | AX |

The camera industry by now was known for the leadership of the Big Five, which comprised Nikon, Olympus, Minolta, Pentax and Canon. Together, they take up anywhere up to 60 percent of worldwide equipment sales for 35mm SLRs. While Leica’s objection to autofocusing was as predictable as we’d historically come to expect from Europeans, Olympus’ opposition was a different matter altogether. Leica was already becoming a boutique brand with low sales numbers, Olympus was competing at a high level of volume sales. Embracing the AF-SLR was far more essential for the Japanese company.

Of the Big Five, the fallout was with Olympus.

Group 1 – Minolta / Nikon / Canon / Pentax

In hindsight these four (including Minolta) benefited the most. After the release of the Maxxum line-up, all three not only worked hard to slipstream behind Minolta with new AF-SLR cameras but all of them revamped their lenses, which of course was a major capitalisation effort. As Minolta changed their lens mount from MD to α (Alpha), the others followed suit beginning with the 1986 changeover from AI to AF-S by Nikon, calling it Nikkor-AF. In the following year (1987), Canon switched from FD to the all-electronic EF mount, calling it EOS. In the same year (1987), Pentax modified the K mount to KAF and bypassed their earlier KF mount used in the ill-fated ME-F.

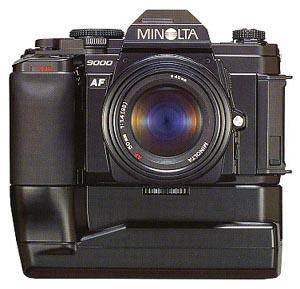

(L-R) Minolta Maxxum 9000, Nikon F4s, Canon EOS-1

Images courtesy of www.friedmanarchives.com (L), www.mir.com.my (M), Canon Corporation (R)

Of the four, Minolta maintained their technological leadership with the best performing autofocusing system, although Nikon and Canon continued to produce high enough numbers to be the bigger sellers. At any rate, Minolta wasn’t far behind. However when it came to applications in the professional field, it was cameras like the Nikon F4s and Canon EOS-1 that held the bragging rights while Minolta’s Maxxum 9000 played a distant second fiddle.

The decision by Nikon and Canon to field pro-grade AF-SLRs can be seen as an endorsement of the prevailing autofocusing technology, that it was more than good enough to be offered to pro users. The fact that they edged out Minolta was likely due to brand loyalty, better body build quality and large range of lenses and other accessories to choose from.

In particular, Nikon enjoyed compatibility advantages because users from the pre-AF days could utilise their latest AF-SLRs with conventional AI-S Nikkor glass while they planned out their purchase of the more modern Nikkor-AF lenses. It was a harder sell for Canon because of the wholesale change they made to the lens mount but aggressive marketing helped them to overcome this initial weakness in a short time. By 1990, both companies had the AF-SLR market wrapped up, commanding a lead that helped transition them smoothly into the digital era.

Group 2 – Olympus

Olympus was clearly the most unsettled of the Big Five. Minolta’s AF-SLR concept divided the company into those who supported and those who did not support it. Right at the centre of this conflict were the Zuiko lenses, which the company held at the highest esteem. For everyone who worked at that level for Olympus, the name Zuiko could only be used to define the highest optical image quality. It’s also a name used to define their competitiveness against its rivals in the industry.

Olympus OM-4 and OM-4Ti

Copyright www.cam2.sakura.ne.jp

Within Olympus, there were those who completely disapprove of the AF-SLR idea. They were a combination of those who believe in the purity of the original mechanisms and those who felt that the mechanical interventions were too disruptive of the lenses at work. There were those who argued that the company needed to compete head-on against the rest of the market and the only way to do so was to revamp the OM System. This of course meant retiring the OM-2S Program, OM-3, OM-4 and also the OM-4Ti, not to mention the consumer-grade OM bodies. It also implied that the whole collection of Zuiko lenses had to be redesigned.

Asking management to basically turn the OM System upside down was simply too much to bear. It wasn’t the cost that mattered – funding the changeover was always there anyway. The problem here was mindset. The idea of discontinuing the OM-3 and OM-4/4Ti was an abominable suggestion, as abominable as replacing all the Zuiko glass. That alone caused a deep rift to occur within the company, pitching some on one side of the fence with the rest on the other side. Perched on the fence itself were those who were too afraid to voice their ideas or that they really didn’t know what was best. After all both sides had arguable points that made sense.

Olympus OM707AF (1986) and OM101PF (1988)

Image courtesy of Olympus Imaging Corporation

In the end after some unproductive dithering, Olympus launched the OM707 in 1986 (OM77AF in North America). It was not too late as some suggested; rather it was far too little. The OM707 was a feeble response from a company capable of so much more and the disappointment in the market was palpable to say the least. Noticeable to fans and followers was the fact that while Olympus had committed themselves to a small range of AF lenses to support the OM707, none of them were labelled Zuiko and that alone spoke volumes of the internal conflict. By withdrawing the use of the Zuiko name was like saying that the management was not in tacit approval of the OM707 or the lenses that support it. Its feature set was also bewildering – there was no direction as to what market segment it was meant to compete in. For example it had the Flash-Synchro (Super-FP) mode, which was designed for pro applications and yet the OM707 was purely an auto-mode camera. Ironically Olympus also decided that the AF lenses would not offer a manual focusing ring. Instead the company saddled the OM707 with a feature called PowerFocus that at best as a timely example of insufficient development work.

The OM707 was a ‘neither here nor there’ camera. It was the result of a company that was pushed and pulled at the same time by people who felt one way but somehow went astray. It had nothing other than the OM part of its name to suggest any relationship with the company’s successful OM System. Notwithstanding the reputation of the lenses, the OM707 was only in name, an Olympus.

Indecision took on the shape of the OM707 but it also paved the way for the company’s fall from grace in almost the same fashion as the Europeans experienced in their fight against the march of the 35mm SLR. Olympus knew that the OM707 alone could not compete in the new AF-SLR segment but instead of adding newer – and more competitive – models (perhaps an OM808), they relied on their legacy models to make their pitch in the market.

Olympus OM-2S Spot/Program

Copyright Andrea Piaggesi

The OM-2S Program was brought in, in 1984, a year before the Maxxum 7000 was unveiled and so by the time the AF-SLR was in full swing, it was already dated. A year before (1983), the OM-3 was introduced together with the OM-4. Both were completely threatened by Minolta’s new AF-SLR range. When the OM-4Ti came out in 1986, the writing was long on the wall. By then its rivals had turned the corner and left the old 35mm SLR behind. Olympus believed in an approach that had outlived its usefulness. Had the AF-SLR come a few years later, history could have proven that the company’s OM-4Ti could outdo the best in the market but that didn’t happen. Once the AF-SLR movement began, there was no stopping it. The cream of the 35mm SLR bunch was, almost overnight, left behind. While Nikon and Canon could sense that, Olympus failed to as they continued to cling on to their technically advanced but outdated OM SLRs.

With no answer in sight, even the most ardent OM users began to move away. Having no choice, they did their cross-upgrades, trading in their OM cameras and lenses and buying into the company’s rival offerings. It would have been quite a painful experience to have to go through and at Olympus, these were the forgettable dark days.

What was important at this point was that Olympus missed the very opportunity to tie the past with the future. The AF-SLR had, in fact, represented the cusp. Because its rivals had embraced it, moving to the digital era was smooth enough. The transition was possible, giving Nikon, Canon and Minolta an important interface between the new digital bodies (DLSRs) and the pre-existing film-AF lenses. Because Olympus didn’t have any of these to rely on, the transition just wasn’t there. The gap to bridge from the traditional OM camera to the DSLR was far too wide and unrealistic. Furthermore there had not been any plans to develop the rumoured Zuiko-AF lenses. What were available were Olympus-AF lenses for the OM707 (and two PF lenses from the OM101) and even so, the range was too narrow to make any sense out of.

By the close of the decade, Olympus was left so far behind that even a belated strategy would be considered too late. By this point, the industry was already experimenting with the Still Video concept. It was a preparation for the real digital age that was just around the block. Choosing between pouring money into developing a competitive AF-SLR or working on Still Video, Olympus chose the latter. And from Still Video, the company at least could make a way into the start of the digital age.

Group 3 – Leica / Rollei / Fujica / Ricoh

Of course Olympus wasn’t the only one to have problems dealing with the AF-SLR. There were others in the same boat except that Olympus was easily the most conspicuous from the headline standpoint. While the company made all the wrong headlines through its reluctance to embrace autofocusing, others like Leica, Rollei and Fujica simply refused to join.

Till today, Leica remains stoic about autofocusing. Their top-ranging digital cameras are still without any AF systems intact. In particular, the iconic M-System has no AF lenses but through the decades, it hadn’t been smooth sailing. From their R-series days and collaboration with Minolta – including the marvellous little CL – Leica had fallen hard financially. Bailouts were not uncommon for this Solm-based company and if it weren’t for their collaboration work with Panasonic, Leica might not even be here today.

Rolleiflex SL2000 F

Copyright Foto-Hobby Rahn GmbH

Rollei lost the plot with autofocusing as well. In fact today the company doesn’t produce cameras anymore. Their last known great cameras included the 35/35S, the SL2000F, SL66 and then the 4004 and 6006 medium-format cameras. Other than the unusual SL2000F, Rollei had once made 35mm SLR cameras although sales weren’t exactly leaping off the charts. When the AF-SLR arrived, they basically languished and all but disappeared. Fujica did not produce any AF-SLRs but as Fujifilm, they picked up the pieces and adopted autofocusing. Although their DSLRs were not market top sellers, the company’s decision to shift to the mirrorless format paid dividends. During the 35mm SLR era, the company’s last range-topper was the ST901 released in 1974. After that, there were more mediocre models such as the ST605, ST701 and so on. When the AF-SLR arrived, Fujica made a quiet withdrawal. The name was all but gone.

Ricoh XR-S, 1986

Copyright www.thecamerasite.net

Ricoh was holding up the other end of the market with value-for-money 35mm SLR offerings, that was, before AF arrived. While they were never in the pro end of the spectrum, Ricoh SLRs were popular for budget buyers and students alike. The KR-5 Super was exceptional value and so were the upper-level XR-S (1986) and XR-M (1987). When Pentax moved to the AF-SLR, Ricoh maintained the K-mount and dropped plans to follow suit. In fact no further SLRs emerged under the Ricoh brand name after the XR-M until they purchased Pentax from Hoya Corporation in 2011.

Group 4 – Contax

While Leica simply refused to have anything to do with autofocusing, Contax had a different thought to the whole subject without distilling the common agreement that the internal of the lens should not be tampered with. And with that the company launched a radical approach to autofocusing that not only stunned the entire industry but at the same time painted themselves into a corner.

The name itself – Contax – is a revered one, no less so than Leica but perhaps with their legacy rooted in Zeiss, they garner considerable attention. Zeiss’ involvement in the 35mm SLR development over the decades is of course legendary and the Contax name was often used here but the latter’s modern history was to be intertwined with Yashica who, through an alliance ratified in 1975, began a line of impressive SLR cameras.

Contax RTS III, 1990

Copyright www.hugorodriguez.com

During this alliance, Contax added a string of medium-scale premium SLR models to form a system around its formidable Porsche-styled RTS (1974) flagship and the much-admired Zeiss lenses, the first of which was the 139Q in 1979. In the following number of years, Yashica added the 137MD (1980), 137MA (1981) including the second-generation RTS II in 1982. Shortly thereafter Yashica themselves were bought out by Kyocera (1983) before the range continued to grow.

The 159MM (1984) arrived as a higher-level model before the 167MT supplanted it two years later (1986). From then till the break of the new millennium, Contax was further fleshed out to include a third-generation RTS III (1990) and a smatter of other cameras. Of course by then, the AF-SLR had already hit the ground running. However fortunes at Contax began to decline and sales became bad enough by 2005 that production and sales of all cameras were halted.

Contax AX, 1996

Copyright www.imageshack.com (L) and foto-hobby_rahn_gmbh (R)

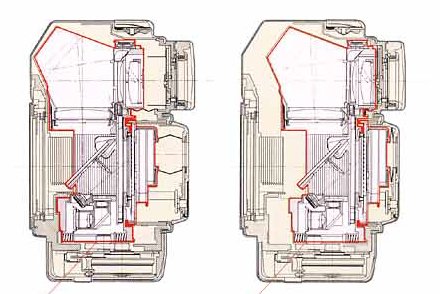

In the ten-year period leading to its discontinuation, Contax introduced its version of the AF-SLR called the AX in 1996. Here was a 35mm AF-SLR that could be used with the existing collection of stellar lenses and still autofocused. The trick was not to move the lens but to shift the film plane, which in principle, wasn’t too different from the large-format view cameras. Of course with the AX, the arrangement was far more complex given that the film plane had to move together with the mirror box as well as the prism/finder assembly. This mechanical 10mm back-and-forth shifting was the heavy lifting work that the other AF-SLRs didn’t have to make do with. This compelled Kyocera to solve three things – speed, torque and precision. There had to be enough speed to get the autofocusing responding fast yet sufficient torque to move that amount of bulk and all of these had to be done with mechanical precision because movement registration was even more critical in the AX.

Contax AX’s movable film plane based autofocusing system

Image courtesy of Kyocera Corporation

For ideal speed and torque, Kyocera resorted to an ultrasonic motor. Such a motor offered low rotation characteristics but also very high torque. It was also well known for its speed. To ensure precise movement, Kyocera’s expertise in ceramic was brought to play. The end result was a unique ceramic guide rod that enables the whole assembly to shift very accurately and smoothly. Using ceramic also offered the advantage of minimal wear thus improving durability to last a lifetime.

Unquestionably the autofocusing on the Contax AX was competitive. From Tom Shea’s preview of the AX written in 1998, the results were rewarding:

“After having used the AX, I am amazed that it is as fast and accurate as it is. It is not as fast as my Canon EOS-1N but it is surprisingly close.”

No matter what such previews might have said glowingly, the AX was a failure. Tom’s article cites a number of technical reasons that related directly to Contax’s choice of autofocusing method, centring on a glaring limitation that prevented the AF range from properly supporting longer focal length lenses as well as lenses that had floating optical arrangements. Interesting these were also mentioned in its own user’s manual.

These may or may not be the only reasons for the AX’s failure. Perhaps Contax’s usual high asking price was another factor. Besides, Zeiss lenses aren’t exactly cheap also. The AX’s attempt to rile the market with its unique offering was good to see but in the end, it faded away as ‘just another failed endeavour.’

Contax N1, 2001

Copyright www.wikimedia.org

Following its dismal failure, Contax reverted to the industry-standard AF-SLR blueprint and came up with the N-series. This too failed but that’s probably because by the time the N1 appeared in 2001, the market was primed sufficiently for DSLR cameras to finally arrive.

Eventually Contax modified the N1 and called it the N-Digital (2002), which went on to become the world’s first full-frame DSLR camera. However the tide of fortune had by then turned against both Kyocera and Contax with unacceptably poor sales returns. Shortly thereafter, the parent company withdrew completely from all camera businesses.

go to next chapter: History Spells the DSLR’s Demise - chapter VII - What the fallout meant